Postcard from Riyadh

Contributor

A Tale of Two Cities

It’s my first time in Riyadh, but it feels like a return. The city, once home to my paternal grandparents, father and uncle, has since become the research object and field of my dissertation-in-progress. Why and how so many Americans expatriated their families for a contract job in Saudi Arabia in the decades bracketing the one marked by “oil crisis” is a phenomenon without much literature. My grandfather, once an HR administrator for the California construction companies Fluor and Bechtel, and later, the Hospital Corporation of America, died before I could ask him about it, and the finer points are hard to retrieve for my 94-year-old grandmother. So I text my dad as I walk across the plaza to King Fahad National Library, sending a picture of the 2015 addition that ingested the original 1986 building. Of course, he doesn’t recognize it. The city of the 1980s has obsolesced in favor of newer construction, especially in this part of Olaya.

He does remember the souk, which remains mostly as it was, though perhaps better oriented to tourists. After a day with my archives, I wait for a Mercedes bus—a recent addition to the city’s public transportation network—to Ad-Dirah. South Asian men fill the seats of the bus that arrives, and the driver asks them to make space for me and another woman boarding. By the time I get to the large plaza held between the Grand Mosque and Qasr al-Hukm, the souk, and Al Masmak Palace, I FaceTime my toddler, who looks past the small version of me on his dad’s phone. “That is a castle,” he says of the Palace-Museum behind me. The Najdi mudbrick fortification is shrouded with a construction textile, printed with images of the building then undergoing restoration.

These are the glimpses of a city perpetually reinventing itself—often through invited guestwork—and where some of the best views of new and old buildings can be caught out of car windows. In the city of closed spaces, as the sociologist Amélie Le Renard has described Riyadh, visitors tend to reproduce images of peripheries. Without leaving one’s compound, being ushered past other secure entrances, invited into offices and homes to be offered too many coffees, the indulgence in facades is inevitable.

Bechtel once enjoyed its own fortification on Beale Street in San Francisco’s financial district: a spare SOM tower from 1967. The building remains, though Bechtel’s offices have since decamped to Virginia. Still, my dissertation brings me home to the Bay Area. On my last trip, I visited the archives of George Shultz at Stanford, reading correspondences from his leadership at the construction giant and from his subsequent promotion to Reagan’s Secretary of State. After Shultz’ own visits to the Kingdom—”many great new buildings in Riyadh!” he remarked to the President after a 1982 trip—he returned home to “the farm” south of San Francisco. I visited mine to the north. Retreading my grandfather’s commute from Marin across the Golden Gate Bridge, I continued up the 101 to Bodega Bay to interview a retired Bechtel engineer, a friend of my maternal grandmother. There are many roads back to Riyadh, and some of them happen to route through my own California upbringing.

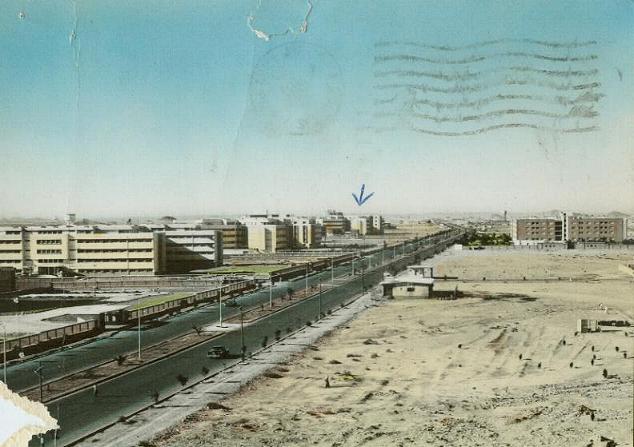

On the highway, or in King Fahad’s library, I think past Harry Printz to Keith Wheeler, another man I can no longer speak to about his work. In 1960, he was the first U.S. Army draftee in Saudi Arabia, stationed at the new Saudi Ministry of Defense and Aviation (MODA) headquarters (↓). The building rose among other modernist government buildings by the Egyptian architect Sayyid Kurayyim along “Airport Road”—a north-south artery retained by the 1972 Doxiadis plan. MODA HQ was redesigned and relocated in the following decades—one of many projects overseen by the US Army Corps of Engineers. Visiting buildings I cannot see, I turn to Wheeler’s testimony. He wrote to his own parents in Corning, California about pushing papers in a hot office “set up for air conditioning” but without the “power nor the personnel to run it.” Remarks about his life in Riyadh are accompanied by armchair criticism of its “ultramodern” architecture:

many of the buildings here in Saudi Arabia are quite new and from a distance would seem to put many of ours to shame when it comes to architecture—but, at a closer inspection many are poorly constructed… Some people blame foreign contractors who come into the country, build quickly and then leave.

Like so many other expats, Wheeler also left at the end of his two-year mission. Bechtel, however, would stay, hoping to contribute something durable to the Kingdom—refineries, an industrial city, a metro not yet open when I visited—or a means to retain its profitable partnership. Riyadh continues to rise through old friendships with American contractors, while their personnel make and recall temporary lives between construction sites.